Inside Jordan Wolfson’s Studio: The Intersection of Art and Technology

Jordan Wolfson’s studio is a curious space, notably devoid of the animated robots that have become synonymous with his work. Nestled within a nondescript industrial park close to Atwater Village in Los Angeles, this 1000-square-foot area serves primarily as a staging ground rather than a workshop; the lifelike animatronic sculptures that have propelled Wolfson into the spotlight are crafted elsewhere, primarily at a larger fabrication facility located in the San Fernando Valley. Scattered across a black folding table are the dismembered, garnet-hued limbs of a boyish puppet titled “Red Sculpture” (2022), while much of the remaining work lies entombed within wooden crates, a testament to a hectic exhibition schedule.

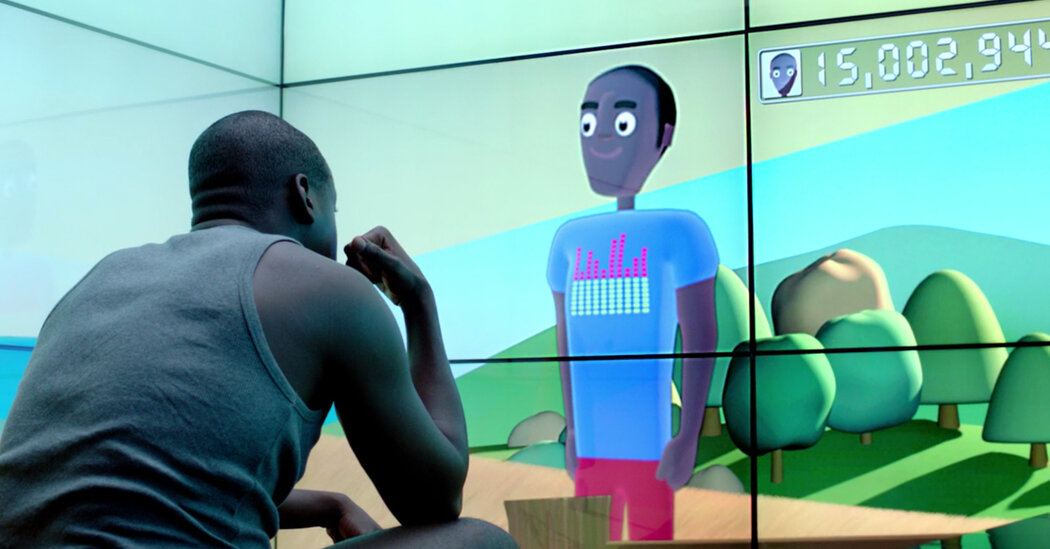

Wolfson has gained notoriety for his sculptural pieces that employ advanced technology in intricate, costly, and occasionally groundbreaking manners, resulting in creations that evoke feelings of dread and unease. His infamous “Female Figure,” a cyborg dancer characterized by blood-red lips and a ghoulish visage, went viral after its appearance in an otherwise vacant David Zwirner Gallery in New York in 2014. Similarly, “Colored Sculpture” (2016), a snarling doll reminiscent of Howdy Doody, whose disjointed body is suspended by a chain and violently thrashed against the floor, garnered widespread attention during its exhibition at the Tate Modern in 2018. These robotic figures are equipped with cutting-edge facial-recognition technology, allowing them to establish intermittent and seemingly deliberate eye contact with viewers, creating an unsettling flirtation with the notion of sentience.

A photograph juxtaposing John F. Kennedy Jr. with one of Wolfson as a child, imagery he recently utilized in an exhibition in Basel, Switzerland, adorns the studio walls. Nearby, a storage area houses reference photos of police officers, a subject Wolfson is currently exploring.

Born in New York and educated at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he earned a B.F.A. in 2003, Wolfson quickly made a name for himself in the art world during the early 2000s, establishing a reputation as a provocateur who challenges liberal sensibilities. One of his most renowned and contentious works, “Real Violence,” showcased at the Whitney Biennial in 2017, required viewers to don virtual reality headsets and noise-canceling headphones. Within this immersive experience, spectators witnessed a grisly scene: a man (a digital representation of Wolfson himself) brutally assaulting another man (a CGI dummy) with a baseball bat until his head graphically explodes. Throughout this harrowing sequence, a third man, unseen but audible through the headphones, sings two Hebrew prayers — a personal touch reflecting Wolfson’s Jewish heritage. “We live in a complex world,” Wolfson remarked during a recent studio visit in October. “I’m simply trying to create art that reflects the times we inhabit. And I find these times to be incredibly violent and, quite frankly, distressing.”

A box of clothing bearing Wolfson’s work sits nearby, including a sweatshirt emblazoned with an image of “House With Face” (2017) and a T-shirt featuring “Female Figure.”

While Wolfson perceives himself as a sincere “witness” to the moral decay of society, his critics adopt a more skeptical stance, grappling with the unsettling nature of his work. In a 2020 profile for The New Yorker, Dana Goodyear probed the intentions behind “Female Figure,” questioning whether the piece expressed misogyny or critiqued it, or potentially even hinted at a veiled confession. “It was impossible to say for sure; Wolfson’s medium is plausible deniability,” she wrote. When confronted with these interpretations, Wolfson dismissed the idea that his sculptures are mere spectacles: “I’m not creating works solely to attract attention or provoke,” he asserted. “That would be an unserious approach to life.”

Currently, many of Wolfson’s larger sculptures are packed away in shipping crates. Among them is “Female Figure” (2014). His most recent endeavor, “Body Sculpture,” is a 36-inch metal cube equipped with intricately designed robotic arms. This new piece, similar to earlier works, performs a range of uncanny gestures, from pointing to gyrating and even “playing itself like a drum.” Wolfson describes these movements as both “silly” and “serious.” “Body Sculpture” is set to premiere at the National Gallery of Australia, which invested $5 million in its creation, on December 9. The project, which began in 2018, originated from a conceptual seed (an idea Wolfson often refers to as “a download,” likening it to an invisible connection to a supercomputer). This concept then evolved into a pitch video presented to several institutions, a strategic approach aimed at securing funding as well as articulating the work’s potential. It has since been in technical production with Los Angeles-based fabricators. Wolfson envisions the piece as an exploration of both the darker and lighter aspects of the human experience, encompassing violence and aggression alongside curiosity and playfulness. When asked if “Body Sculpture” is meant to represent a specific individual or entity, he confidently replies, “It’s a surrogate for you.” To complement its unveiling, Wolfson has selected an array of works from the National Gallery’s collection, featuring pieces by Robert Mapplethorpe, Claes Oldenburg, Diane Arbus, Andy Warhol, Elaine Sturtevant, and Donald Judd.

During a visit to his studio in October, Wolfson engaged with T’s artist questionnaire amidst the vibrant lighting and an unusual misty atmosphere, accompanied by the melodic chirping of a hidden cricket. We sat at a table adjacent to a wall filled with peculiar AI-generated imagery (a process he was experimenting with using OpenAI’s DALL-E imaging system), which included a bowl of apples entangled with chains and a leather-gloved hand holding a cross.

When did you first feel comfortable calling yourself a professional artist?

I considered myself a professional artist from the moment I began creating art. I distinctly remember feeling that way by the age of 18, motivated by my seriousness and commitment to the craft. While one could argue that a professional is someone who earns a living from their work, I had sold a few paintings earlier in my life. However, I believe anyone who dedicates themselves seriously to their art can rightfully identify as a professional. But who am I to judge what anyone chooses to call themselves?

What was the first work you ever sold?

I had a gallery show during high school and sold a painting. I deeply regret selling it, as it’s a piece I would have liked to keep. In fact, I wish I could retain much more of my work.

What was the painting?

It depicted a photograph from Life magazine, a well-known publication from the ’50s and ’60s. The image featured a man in overalls, standing and gazing into the light — it’s challenging to articulate. However, there has always been an element of Americanness in my work, focusing on themes of American life and culture. It was a distinctly American image.

I’d like to hear more about this idea of Americanness and how that plays into your work now.

Though I’ve spent time in Europe, I never found it conducive to my artistic practice. For reasons I can’t quite pinpoint, I’ve consistently felt more at home creating art here in the U.S., and I’ve always considered it my target audience. It’s easier to produce art when you’re situated in the eye of the storm rather than standing outside of it.

Do you feel like you’re in the center of the storm now?

Yes. However, in my recent works, I find myself looking inward, focusing more on physicality rather than topical or historical American content.

Why do you think people often focus on the violence in your work?

My art explores the human condition. We inhabit a complex world with a rich history of violence. I don’t condone this violence, nor do I embrace it, but in taking my role as an artist seriously, I strive to reflect the reality of what I observe. Do you want a witness who will shy away from depicting the truth of their observations?

Do you think an artist has a social responsibility to bear witness?

I believe artists should feel free to create whatever resonates with them. Personally, I’ve sought to bear witness in the most honest ways possible, engaging with various subject matters.

What is your process of creating a new work? Where do you start?

Ideas often come to me rapidly — sometimes within just a few minutes — and I can conceptualize an entire piece in that timeframe.

And what is the idea? Is it an image of the piece?

It’s almost like … Have you ever typed something into ChatGPT? It quickly generates a detailed response. I can’t quite describe it, but it feels similar to that. Part of my role involves preparing myself to create, whether that means clearing my mind from a distraction like stubbing my toe or dealing with a flat tire. I’ve been meditating for about 14 years, and I refuse to engage with my work unless I’ve taken the time to meditate beforehand. This practice extends to meetings and interviews as well.

So you meditate every day?

Sometimes multiple times a day.

What is your typical day like?

I start my day with a walk with my dog, followed by coffee and breakfast. Then we sit in the grass, and I meditate. Afterward, I connect with everyone to understand the day’s agenda. Usually, I meet with an artist named Russell Barsanti, my primary technical collaborator. Our sessions typically last about 3 to 4 hours, filled with driving around and visiting various fabricators. We engage in discussions about exciting elements, such as the surface of a sculpture. I also maintain an office at home, where I try to exercise and enjoy evenings with friends, often reading before bed.

What are you reading now?

I’m currently engrossed in the screenplay for Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona” (1966). It’s a masterpiece.

Are you binge-watching any shows right now?

No, I don’t watch television, but I do enjoy films. The last intriguing movie I viewed was “Minority Report” (2002).

What’s your worst habit?

Not trusting myself. I constantly strive to overcome that.

What embarrasses you?

Pretty much everything. Many situations can lead to embarrassment for me — not knowing something, saying the wrong thing, feeling foolish, or being overly eager for someone’s approval. Even having food stuck in my teeth can make me cringe. I’ve certainly been unintentionally rude to people in the past, and that has embarrassed me as well.

What’s the last thing that made you cry?

I spent time with my mother’s body after she passed away. I stayed with her for a while.

I’m sorry. Was that recent?

Yes, it happened in August.

Has a work of art ever made you cry?

Yes, [Caravaggio’s] “The Calling of St. Matthew” [1599-1600] had that effect on me.

Is there an artist whose work you really admire or feel envious of?

There are several prominent sculptors from the generations before mine, such as Katharina Fritsch, Charles Ray, Paul McCarthy, and Jeff Koons. Additionally, I appreciate many contemporary artists, including Carol Bove, Rosemarie Trockel, and Isa Genzken. I feel incredibly fortunate to be part of this world and to connect with talented practitioners.

Do you talk to other artists regularly?

Absolutely. It’s remarkable; I was so invested in art as a young person, and now I’m fortunate enough to call many artists I once idolized my friends and acquaintances. It’s truly special. The individual I’d have most liked to meet — and I actually had lunch with [his collaborator] Paul McCarthy last weekend — was the late visual artist Mike Kelley.

How do you know when a piece is finished?

It often comes down to a generative feeling. When I observe a piece, it transitions into a state of stasis. At that point, there’s either an increased or decreased energy, but it must resonate the right way, maintaining the appropriate tone and attitude without collapsing into moralism or didacticism. There exists a certain frequency of vagueness or ambiguity, and the piece captures that essence. It should also evoke something I haven’t seen before, either in the work or within my own practice. I strive for that. The goal isn’t necessarily for the work to be original, but rather to possess a strong tension.

Do you consider your robotic sculptures to be sentient or possessing the potential for sentience?

People often ask this question. I find myself boring in my responses regarding my relationship with these works. It’s not a Pygmalion dynamic for me; rather, my approach is quite pragmatic. I demand a great deal from them—not as individual entities, but as artworks. I believe that if I anthropomorphize them or develop an emotional attachment due to their figurative or humanoid nature, it would distract me from pushing the work to its limits. I recall during the programming phase of “Female Figure,” while it was installed atop a furniture warehouse, I found myself alone with it. When it unexpectedly looked into the mirror and up at me, I screamed, bolted out, and drove home. After that experience, I aimed to maintain a neutral relationship with it.